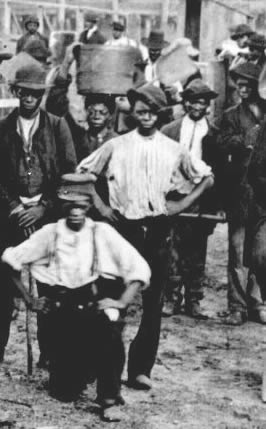

“If It Were Not For My Trust in Christ I Do Not Know How I Could Have Endured It”: Testimony from Victims of New York’s Draft Riots, July, 1863

Between July 13 and 16, 1863, the largest riots the United States had yet seen shook New York City. In the so-called Civil War draft riots, the city’s poor white working people, many of them Irish immigrants, bloodily protested the federally-imposed draft requiring all men to enlist in the Union Army. The rioters took out their rage on their perceived enemies: the Republicans whose wealth allowed them to purchase substitutes for military service, and the poor African Americans—their rivals in the city’s labor market—for whom the war was being fought. On July 20, four days after federal troops put down the uprising, a group of Wall Street businessmen formed a committee to aid New York’s devastated black community. The Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People Suffering from the Late Riots gathered and distributed funds, and collected the following testimony.

Abraham Franklin

This young man who was murdered by the mob on the corner of Twenty-seventh St., and Seventh avenue, was a quiet, inoffensive man, 23 years of age, of unexceptionable character, and a member of the Zion African Church in this city. Although a cripple, he earned a living for himself and his mother by serving a gentleman in the capacity of a coachman. A short time previous to the assault upon his person he called upon his mother to see if anything could be done by him for her safety. The old lady, who is noted for her piety and her Christian deportment, said she considered herself perfectly safe; but if her time to die had come, she was ready to die. Her son then knelt down by her side, and implored the protection of Heaven in behalf of his mother. The old lady was affected to tears, and said to our informant that it seemed to her that good angels were present in the room.

Scarcely had the supplicant risen from his knees, when the mob broke down the door, seized him, beat him over the head and face with fists and clubs, and then hanged him in the presence of his mother.

While they were engaged, the military came and drove them away, cutting down the body of Franklin who raised his arm once slightly and gave a few signs of life.

The military then moved on to quell other riots, when the mob returned and again suspended the now probably lifeless body of Franklin, cutting out pieces of flesh and otherwise mutilating it.

Peter Heuston.

Peter Heuston, sixty-three years of age, a Mohawk Indian, with dark complexion and straight black hair, who has for several years been a resident of this city, at the corner of Rosevelt and Oak streets, and who has obtained a livelihood as a laborer, proved a victim to the late riots.

His wife died about three weeks before the riots, leaving with her husband an only child, a little girl named Lavinia, aged eight years, whom the Merchants' Committee have undertaken to adopt with a view of affording her a guardianship and an education. Heuston served with the New York Volunteers in the Mexican War, and has always been loyal to our government. He was brutally attacked on the 13th of July by a gang of ruffians who evidently thought him to be of the African race because of his dark complexion. He died within four days at Bellevue hospital from his injuries....

Wm. Henry Nichols

Died July 16th, from injuries received at the hands of the rioters on the 15th of July.

Mrs. Statts, his mother, tells this story:—

The father of Wm. Henry died some years ago, and the boy has since, by good behavior, with persevering industry, earned his own living; he was a communicant of the Protestant Episcopal Church, in good standing. I had arrived from Philadelphia, the previous Monday evening, before any indications of the riot were known, and was temporarily stopping, on Wednesday, July 15th, at the house of my son, No.147 East 28th street.

At 3 o’clock of that day the mob arrived and immediately commenced an attack with terrific yells, and a shower of stones and bricks, upon the house. In the next room to where I was sitting was a poor woman, who had been confined with a child on Sunday, three days previous. Some of the rioters broke through the front door with pick axes, and came rushing into the room where this poor woman lay, and commenced to pull the clothes from off her. Knowing that their rate was chiefly directed against men, I hid my son behind me and ran with him through the back door, down into the basement. In a little while I saw the innocent babe, of three days old, come crashing down into the yard; some of the rioters had dashed it out of the back window, killing it instantly. In a few minutes streams of water came pouring down into the basement, the mob had cut the Croton water-pipes with their axes. Fearing we should be drowned in the cellar, (there were ten of us, mostly women and children, there) I took my boy and flew past the dead body of the babe, out to the rear of the yard, hoping to escape with him through an open lot into 29th street; but here, to our horror and dismay, we met the mob again; I, with my son, had climbed the fence, but the sight of those maddened demons so affected me that I fell back, fainting, into the yard; my son jumped down from the fence to pick me up, and a dozen of the rioters came leaping over the fence after him. As they surrounded us my son exclaimed, “save my mother, gentlemen, if you kill me.” "Well, we will kill you," they answered; and with that two ruffians seized him, each taking hold of an arm, while a third, armed with a crow-bar, calling upon them to stand and hold his arms apart, deliberately struck him a heavy blow over the head, felling him, like a bullock, to the ground. (He died in the N.Y. hospital two days after.) I believe if I were to live a hundred years I would never forget that scene, or cease to hear the horrid voices of that demoniacal mob resounding in my ears.

They then drove me over the fence, and as I was passing over, one of the mob seized a pocket-book, which he saw in my bosom, and in his eagerness to get it tore the dress off my shoulders.

I, with several others, then ran to the 29th street Station House, but we were here refused admittance, and told by the Captain that we were frightened without cause. A gentleman who accompanied us told the Captain of the facts, but we were all turned away.

I then went down to my husband’s, in Broome Street, and there I encountered another mob, who, before I could escape commenced stoning me. They beat me severely.

I reached the house but found my husband had left for Rahway. Scarcely knowing what I did, I then wandered, bewildered and sick, in the direction he had taken, and towards Philadelphia, and reached Jersey City, where a kind, Christian gentleman, Mr. Arthur Lynch, found me, and took me to his house, where his good wife nursed me for over two weeks, while I was very sick.

I am a member of the Baptist Church, and if it were not for my trust in Christ I do not know how I could have endured it.

Interesting Statement

I am a whitewasher by trade, and have worked, boy and man, in this city for sixty-three years. On Tuesday afternoon I was standing on the corner of Thirtieth street and Second avenue, when a crowd of young men came running along shouting “Here’s a nigger, here’s a nigger.” Almost before I knew of their intention, I was knocked down, kicked here and there, badgered and battered without mercy, until a cry of “the Peelers are coming” was raised; and I was left almost senseless, with a broken arm and a face covered with blood, on the railroad track. I was helped home on a cart by the officers, who were very kind to me, and gave me some brandy before I got home. I entertain no malice and have no desire for revenge against these people. Why should they hurt me or my colored brethren? We are poor men like them; we work hard and get but little for it. I was born in this State and have lived here all my life, and it seems hard, very hard, that we should be knocked down and kept out of work just to oblige folks who won’t work themselves and don’t want others to work.

We asked him if it was true that the negroes had formed any organization for self-defence, as was rumored. He said no; that, so far as he knew, “they all desire to keep out of the way, to be quiet, and do their best toward allaying the excitement in the City.”

The room in which the old man was lying was small, but it was the kitchen, sitting-room, bedroom and garret of four grown persons and five children.

Instances of this kind might be multiplied by the dozen, gathered from the lips of suffering men, who, though wounded and maimed by ruffians and rioters, are content to be left alone, and wish for no revenge.

Burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum

Our attention was early called to this outrage by a number of letters from the relatives and friends of the children, anxiously inquiring as to the whereabouts of the little ones. It is well known that as soon as the Bull’s Head Hotel had been attacked by the mob, their next destination was the Colored Orphan Asylum, on Fifth Avenue, near Forty-third street. The crowd had swelled to an immense number at this locality, and went professionally to work in order to destroy the building, and, at the same time, to make appropriation of any thing of value by which they might aggrandize themselves. About four hundred entered the house at the time, and immediately proceeded to pitch out beds, chairs, tables, and every species of furniture, which were eagerly seized by the crowd below, and carried off. When all was taken, the house was then set on fire, and shared the fate of the others.

While the rioters were clamoring for admittance at the front door, the Matron and Superintendent were quietly and rapidly conducting the children out the back yard, down to the police station. They remained there until Thursday, (the burning of the Asylum occurred on Monday, July 13th, when they were all removed in safety to Blackwell’s Island, where they still remain.

There were 230 children between the ages of 4 and 12 years in the home at the time of the riot.

...

The buildings were of brick and were substantial and commodious structures. A number of fine shade trees and flowering shrubs adorned the ample play grounds and front court yard, and a well built fence surrounded the whole.

The main buildings were burned. The trees were girdled by cutting with axes; the shrubs uprooted, and the fence carried away. All was destroyed except the residence of Mr. Davis [the superintendent], which was sacked.

White Women

Some four or five white women, wives of colored men applied for relief. In every instance they had been severly dealt with by the mob. One Irish woman, Mrs. C. was so persecuted and shunned by every one, that when she called for aid, she was nearly insane.

[Source: Report of the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People, Suffering From the Late Riots in the City of New York. (New York, 1863).]

The British cover to Kathryn Stockett’s novel The Help – about the experiences of black maids in Mississippi in the early 1960s – is a period photograph of a little white girl in a pushchair flanked by two black women in starched white uniforms – the 'help’ of the book’s title.

The British cover to Kathryn Stockett’s novel The Help – about the experiences of black maids in Mississippi in the early 1960s – is a period photograph of a little white girl in a pushchair flanked by two black women in starched white uniforms – the 'help’ of the book’s title. The Help took five years to write, got at least 45 rejection letters from agents, and when finally published went straight into the American bestseller lists. It has sold a quarter of a million copies so far in the US, and is still selling briskly.

The Help took five years to write, got at least 45 rejection letters from agents, and when finally published went straight into the American bestseller lists. It has sold a quarter of a million copies so far in the US, and is still selling briskly.

It’s a risky thing to do – being white and well off – to write in a black voice, especially writing in the vernacular. The dialect Stockett employs is like another language; it is a clever act of ventriloquism, which draws you completely into a world of okra and fried chicken and peach cobbler, but a world with menacing undertones. It is history on the cusp of change, and Stockett has captured the unique complexities of the relationships between white women who will entrust the upbringing of their babies to someone with whom they will not share a bathroom. In the book Aibileen always leaves the families she works for as soon as the child she’s looking after starts to see her in a different light.

It’s a risky thing to do – being white and well off – to write in a black voice, especially writing in the vernacular. The dialect Stockett employs is like another language; it is a clever act of ventriloquism, which draws you completely into a world of okra and fried chicken and peach cobbler, but a world with menacing undertones. It is history on the cusp of change, and Stockett has captured the unique complexities of the relationships between white women who will entrust the upbringing of their babies to someone with whom they will not share a bathroom. In the book Aibileen always leaves the families she works for as soon as the child she’s looking after starts to see her in a different light. 'I want to stop that moment from coming – and it come in ever white child’s life – when they start to think that coloured folks ain’t as good as whites.’ (source: UK Telegraph, by Jessamy Calkin)

'I want to stop that moment from coming – and it come in ever white child’s life – when they start to think that coloured folks ain’t as good as whites.’ (source: UK Telegraph, by Jessamy Calkin)

“What’s interesting to me is how the memory of this got lost,” Blight said. “It is, in effect, the first Memorial Day and it was primarily led by former slaves in Charleston.”

“What’s interesting to me is how the memory of this got lost,” Blight said. “It is, in effect, the first Memorial Day and it was primarily led by former slaves in Charleston.”